CT scanning is transforming Alberta’s paleontology by converting physical fossils into dynamic, immortal digital data, not just creating 3D images.

- This “datafication” allows for non-destructive analysis of delicate structures like skin and organs, revealing secrets without damaging the original specimen.

- Digital twins of fossils can be 3D printed and shared globally, democratizing research and education far beyond museum walls.

Recommendation: Think of Alberta’s fossils less as static objects and more as the source code for a new, digital prehistoric world accessible to everyone.

The classic image of paleontology is one of patience and preservation: a fragile fossil, carefully excavated and painstakingly cleaned, destined to sit behind glass. It is a relic of a lost world, a singular object locked in time and space. For decades, the primary challenge has been to study these ancient remains without destroying them. We have learned much from these silent stones, but their stories have always been constrained by their physical fragility.

The conventional wisdom has been that technology’s role is to improve the tools of extraction and preservation. Better brushes, stronger glues, more precise drills. But what if this entire paradigm is outdated? What if the true technological revolution isn’t about better ways to handle the bone, but about transcending the bone altogether? This is the reality unfolding in Alberta, a global epicentre for dinosaur discoveries. Here, innovators are not just unearthing fossils; they are data-mining them.

This article moves beyond the familiar narrative of finding dinosaurs. It explores the profound shift from paleontology as a study of objects to a discipline of data management. By transforming petrified remains into high-fidelity digital twins, Alberta’s scientists are not just looking inside fossils—they are liberating them from their physical constraints. This is the dawn of computational paleontology, where a fossil found in the Badlands can be analyzed simultaneously by researchers in Tokyo, London, and your local library, ushering in an era of open-source discovery.

We will explore how this digital revolution is reshaping every facet of the field. From the initial discovery of incredibly preserved “dino-mummies” to the way amateurs, tourists, and institutions contribute to building this new digital Jurassic Park, we are witnessing a fundamental change in our relationship with the prehistoric past.

Summary: The Future of Fossils: Unlocking Alberta’s Prehistoric Data

- Skin and Scales: How Do Scientists Find Mummified Dinosaur Parts?

- Replicas vs Real: How 3D Printing Helps Share Fossils Globally?

- Digging for a Living: How to Become a Paleontologist in Alberta?

- Amateur Finds: Can Regular People Contribute to Scientific Discovery?

- Donations vs Taxes: Who Funds the Digs in the Badlands?

- How Can Tourists Participate in Citizen Science Projects During Their Stay?

- Black Beauty to the Burgess Shale: Which Exhibits Should You Prioritize?

- Why is Dinosaur Provincial Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

Skin and Scales: How Do Scientists Find Mummified Dinosaur Parts?

Finding a dinosaur bone is rare. Finding a skeleton is exceptional. But discovering a “mummified” dinosaur—a fossil so exquisitely preserved that it includes skin, armour, and even stomach contents—is a paleontological jackpot. These are not discoveries made by chance alone; they are the product of unique geological conditions and, increasingly, industrial-scale excavation. The most famous recent example from Alberta, a nodosaur named Borealopelta markmitchelli, was not found by a paleontologist with a brush, but by a heavy-equipment operator at an oil sands mine.

This remarkable specimen was preserved when the carcass washed out to sea, sank into marine sediment, and was rapidly buried in an environment lacking oxygen. This process prevented decay and allowed minerals to pervasively replace soft tissues over millions of years. The result is a near-perfect, three-dimensional fossil. Finding these requires recognizing subtle differences in the rock during massive earth-moving operations, where operators are trained to spot anomalies.

Once identified, the process is painstakingly slow. The Borealopelta specimen was so complete that, according to a museum technician, it took over 7,000 hours of work to prepare the fossil for study. It is during this preparation that CT scanners become indispensable. They allow technicians to “see” through the rock, mapping out the delicate fossilized skin and armour plates before a single physical tool touches them, ensuring these irreplaceable features are not accidentally destroyed. This is the first step in the fossil’s datafication: creating a digital roadmap for its physical rebirth.

Replicas vs Real: How 3D Printing Helps Share Fossils Globally?

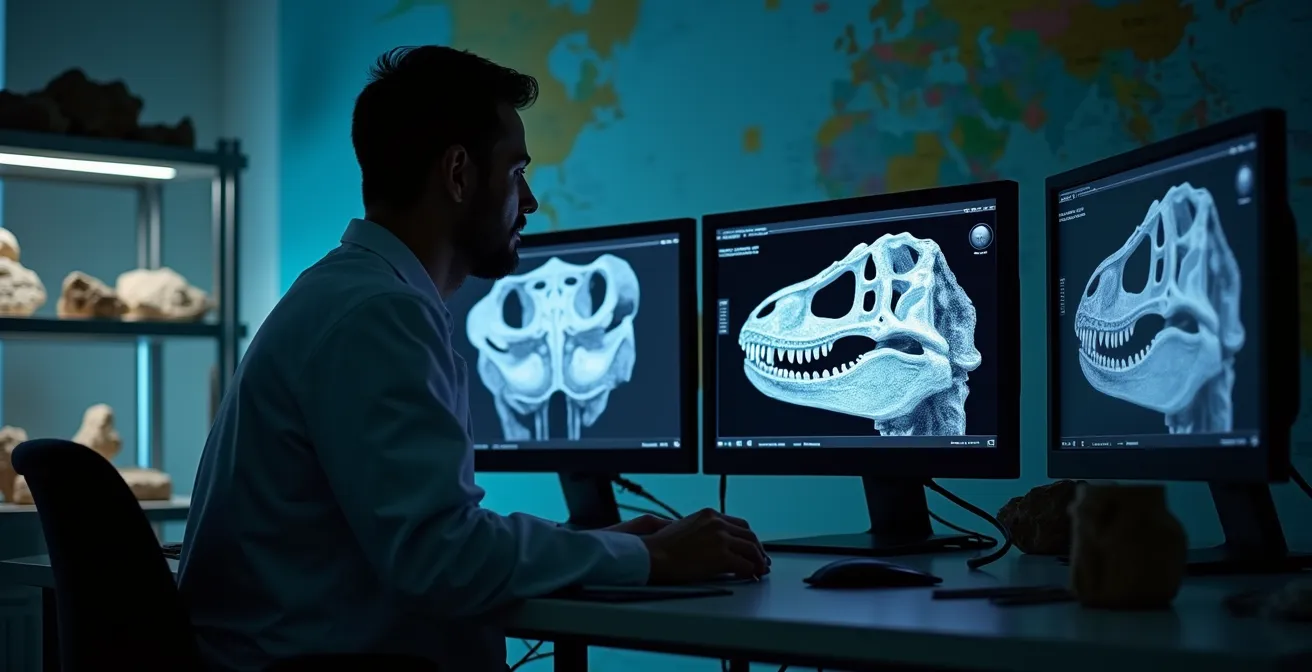

For centuries, a fossil’s knowledge was locked to its physical location. A researcher had to travel to the museum, or the museum had to risk shipping a priceless, fragile object. This paradigm is being shattered by the combination of CT scanning and 3D printing. The process represents a fundamental shift: the fossil is no longer just an object, but a source of data. A CT scanner bombards the fossil with X-rays from every angle, and a computer reconstructs these slices into a minutely detailed 3D model—a perfect digital twin.

This digital file achieves what the physical fossil never could: it is immortal, easily shareable, and infinitely replicable. Researchers across the globe can download the file and analyze the dinosaur’s internal bone structure, map nerve pathways, or study bite mechanics on their computers. This “open-source paleontology” accelerates the pace of discovery exponentially. Furthermore, the digital model can be sent to a 3D printer anywhere in the world, creating a pitch-perfect replica for educational programs or further research.

This paragraph introduces the concept of the digital twin. To better understand this, the illustration below shows the tangible output of this process.

As seen here, these replicas allow for hands-on experiences that would be impossible with the original. The investment in this technology is significant; CT scanning costs can range into the hundreds of dollars per hour, but the return—global access and the preservation of data—is invaluable. It effectively democratizes access to Alberta’s prehistoric treasures.

Digging for a Living: How to Become a Paleontologist in Alberta?

The path to becoming a paleontologist in a fossil-rich province like Alberta is one of passion, advanced education, and often, extreme patience. While the public image is one of thrilling discovery in the sun-drenched Badlands, the reality involves rigorous academic work. A career typically begins with a Bachelor of Science in geology or biology, followed by a Master’s degree and, for research and academic positions, a Ph.D. specializing in a specific area of paleontology.

However, the field is broader than just “dinosaur hunting.” Careers exist in fossil preparation, museum curation, collections management, and education. The case of Mark Mitchell, a technician at the Royal Tyrrell Museum, is a prime example. He spent over five years—a significant portion of a career—meticulously preparing the Borealopelta fossil using microscopic vibrating tools. This is a highly skilled, technical profession that combines scientific knowledge with artistic precision.

The reward for this dedication is the chance to be the first human to see a creature that has been hidden for millions of years. As one researcher at the Royal Tyrrell Museum described the feeling of working on such a well-preserved specimen, “You don’t need to use much imagination to reconstruct it; if you just squint your eyes a bit, you could almost believe it was sleeping.” This human connection to the distant past is the driving force for many in the field. For those aspiring to join their ranks, universities in Alberta offer strong programs, but volunteer work and field school experience are critical for building a career in this competitive discipline.

Amateur Finds: Can Regular People Contribute to Scientific Discovery?

Absolutely. While professional paleontologists lead the charge, some of Alberta’s most significant fossil discoveries have been made by ordinary people. The province’s geology, combined with extensive industrial activity like mining and construction, means that ancient remains are constantly being exposed. The story of Shawn Funk, the excavator operator who discovered the Borealopelta nodosaur, is a powerful illustration of the role citizen scientists can play.

Funk, working at the Millennium Mine, recognized that the object he struck was no ordinary rock. His awareness and quick reporting triggered the scientific response that led to the recovery of one of the best-preserved dinosaurs ever found. This highlights a crucial aspect of Alberta’s fossil management: public education and cooperation are vital. Industrial workers, hikers, and even tourists are the eyes and ears on the ground across a vast landscape.

However, it is critical for any amateur fossil hunter to understand the law. In Alberta, fossils are the property of the Crown and cannot be kept. Any discovery must be reported to the Royal Tyrrell Museum. This ensures that finds of scientific value are properly excavated, preserved, and studied for the benefit of all. Rather than keeping a souvenir, the finder gets something far greater: their name in the annals of science and the knowledge that they have contributed to our collective understanding of prehistoric life. With the Royal Tyrrell Museum attracting an average of 450,000 annual visitors, the public’s fascination is a powerful engine for potential discoveries.

Donations vs Taxes: Who Funds the Digs in the Badlands?

The high-tech world of modern paleontology, with its expensive CT scanners and time-consuming excavations, carries a significant price tag. The funding model in Alberta is a hybrid, relying on a foundation of public investment supplemented by corporate and private support. The primary institution, the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, is a provincial entity. It was established with public funds; for instance, the provincially funded facility had a capital cost of $30 million at its inception.

This government funding covers the museum’s core operations, staff, and a significant portion of its research. It is a direct investment by the taxpayers of Alberta in the preservation and study of their unique natural heritage. This public mandate is what allows the museum to enforce the fossil protection laws and act as the central repository for all discoveries in the province. The funding ensures that scientific priorities, rather than commercial ones, drive the research agenda.

The vast landscapes of the Alberta badlands require significant resources to explore. The image below gives a sense of the scale of a typical paleontological excavation site.

In addition to taxes, corporate partnerships play a crucial role. Energy and mining companies, whose operations often lead to fossil discoveries, frequently collaborate with museums. They may provide funding for the excavation of a fossil found on their land or support specific exhibits and research programs. Finally, private donations and museum memberships from enthusiastic individuals add another layer of support, often funding special projects or educational outreach. It’s a collaborative ecosystem built on a bedrock of public funding.

How Can Tourists Participate in Citizen Science Projects During Their Stay?

For visitors to Alberta, the dream of being part of a dinosaur discovery doesn’t have to be a passive one. The Royal Tyrrell Museum and other organizations have created numerous avenues for tourists to engage directly with paleontological science. This is more than just looking at exhibits; it’s about actively participating in the process of discovery and research, transforming a vacation into a contribution to science.

The museum’s location in the heart of the Badlands provides a natural laboratory for public engagement. Through a variety of registered programs, visitors can move from observer to participant. These hands-on experiences are designed to be both educational and genuinely helpful to the museum’s ongoing work, whether by helping to find small fossils or learning the delicate techniques used by preparators in the lab. The museum even operates a satellite field station in nearby Dinosaur Provincial Park, where new specimens are found each year, offering a direct window into active research sites.

These opportunities bridge the gap between academic science and public curiosity, creating a more engaged and informed populace that understands and values the importance of preserving this heritage. For any tech-savvy traveler looking for a truly unique experience, participating in one of these programs is a chance to step into the story.

Your Action Plan: Engaging with Paleontology in Alberta

- Participate in dinosaur excavations through official museum programs.

- Join fossil preparation workshops to learn hands-on laboratory techniques.

- Take guided hikes in the surrounding badlands with expert paleontologists who can identify local geology and fossils.

- Watch fossils being prepared in real-time through the museum’s public preparation laboratory window.

- Explore interactive science experiments and digital fossil displays within the museum’s main exhibit halls.

Black Beauty to the Burgess Shale: Which Exhibits Should You Prioritize?

A visit to Alberta’s Royal Tyrrell Museum can be overwhelming due to the sheer scale of its collection. To maximize the experience, especially for those interested in the fusion of technology and paleontology, certain exhibits should be at the top of your list. While classics like “Black Beauty,” the dark-hued Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton, are awe-inspiring, the true vision of the future lies in exhibits like that of the Borealopelta markmitchelli.

The Borealopelta display is the pinnacle of tech-driven paleontology. The fossil itself is a marvel, but the exhibit goes further, incorporating digital reconstructions of the animal’s appearance with unprecedented precision. Because the skin, scale patterns, and armour are so well preserved, scientists were able to create a highly accurate digital model, giving us the most realistic glimpse of what this 1.3-ton creature actually looked like. It’s a direct result of the datafication process, moving from bone to pixels to life-like rendering.

This exhibit is powerful because it juxtaposes the ancient and the futuristic. You see the physical stone, then you see the digital life that was extracted from it. This contrast highlights the fragility of the original material. As fossil preparator Mark Mitchell noted about the bone, “The bone itself is very chalky. It’s almost like drywall plaster — you can almost scratch it with your fingernail in places.”

The bone itself is very chalky. It’s almost like drywall plaster — you can almost scratch it with your fingernail in places

– Mark Mitchell, Interview with Inverse

Prioritizing this exhibit, alongside the Burgess Shale display which showcases some of Earth’s earliest and strangest life forms, provides a comprehensive view of paleontological discovery—from the dawn of complex life to the dawn of the digital dinosaur.

Key takeaways

- The future of paleontology in Alberta lies in the “datafication” of fossils, turning physical relics into shareable, analyzable digital twins.

- Citizen science is not a novelty but a core pillar of discovery, with industrial workers and tourists playing a vital role.

- The Royal Tyrrell Museum acts as the central hub, powered by public funding, for a high-tech ecosystem that preserves and democratizes Alberta’s prehistoric heritage.

Why is Dinosaur Provincial Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

Dinosaur Provincial Park’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site is not just about the quantity of fossils, but their unparalleled quality, density, and diversity. This relatively small patch of the Alberta Badlands has produced an astonishing concentration of Late Cretaceous dinosaur remains, representing over 40 species. It is arguably the most significant site of its kind in the world, providing an almost complete picture of an entire ecosystem from 75 million years ago.

The reason for this richness is geological. The sediments that form the park’s iconic hoodoos were deposited by ancient rivers on a coastal plain. This environment was perfect for rapidly burying animal remains, leading to exceptional preservation. The ongoing erosion in the park continually exposes new fossils, making it a site of perpetual discovery. This isn’t a static historical site; it’s an active, evolving scientific laboratory.

The park’s global importance is further cemented by its connection to the Royal Tyrrell Museum, whose collection is built upon the discoveries made here. For context on the sheer volume, the museum’s personal collection includes over 160,000 cataloged fossils, with a significant portion originating from the park. This incredible density of information, covering everything from giant tyrannosaurs to tiny mammals, fish, and plants, is what makes the park a truly irreplaceable window into the Age of Dinosaurs, justifying its protection on a global scale.

By embracing a future where fossils are as much data as they are bone, Alberta is not only safeguarding its prehistoric past but is actively building the tools for its universal, digital future. The next time you see a dinosaur skeleton, consider it not as an endpoint, but as the first node in a vast and growing network of global discovery. The best way to experience this paradigm shift firsthand is to visit the Royal Tyrrell Museum and Dinosaur Provincial Park to witness the genesis of the digital Jurassic Park.